“He told me, ‘This is a prime land, a very good plot. We can give you a freehold title instead of a leasehold, but there’s a condition,” Patrick says. That “condition” was a bribe: 20 million Uganda shillings.

Residents accuse officials of demanding bribes, leaving hundreds of land titles pending, adding to the growing frustration.

By Willy Chowoo

Gulu, Uganda |November 2, 2025. For over two decades, Aluku Charles, 77, a resident of Kanyagoga B Cell in Gulu City, has been caught in a web of bureaucratic delays in his quest to obtain a land title. Aluku began the process in 2002, hopeful that he would soon secure ownership documents for the land he inherited from his late father.

Twelve years later, in 2012, his file — No. 35/PPC/2012. was among 37 applications approved by the Physical Planning Committee of the former Gulu Municipality on October 29, 2012. Yet, more than a decade since that approval, Aluku’s file has never progressed beyond the city level.

“When I ask for my file, they go and look around, but never bring it. They keep telling me to come back. I am now confused and don’t know what to do,” Aluku says, visibly weary after years of fruitless follow-ups.

He recalls that on June 29, 2013, the Department of Lands and Surveys under the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development cleared him to conduct a land survey, a step that should have brought him closer to receiving his title. But to this day, the process has stalled as he can’t locate his file.

“I want to get my title as soon as yesterday. Nobody wants to tell me what should be done. I am frustrated,” he adds, shaking his head in disbelief.

Many residents in Gulu City say attempts to register their land have been met with endless delays. Applicants report waiting for months or years without progress, with some alleging that files are deliberately misplaced until money changes hands.

Missing Files

Aluku’s story is far from unique. Akena Nixon (not his real name), another elderly resident from Kasubi Cell in Gulu City, has been struggling to register two plots of land since the early 2020s. He says the absence of titles has disrupted his plans to develop the land.

“I can’t construct on these plots without titles, and this has completely disorganised my plans,” Akena laments.

Their experiences mirror those of many landowners across Gulu city who continue to face systemic inefficiencies, corruption, and lost documentation in the land registration process. Some of the files are being eaten by termites, eaten up by dust, and several people continue to give up registering their land.

Another land victim is only identified as Patrick due to the sensitivity of the issue, a resident of Laroo-Pece. When Patrick first returned to the district land office to trace the family’s file, the new secretary couldn’t locate it. “He told us his predecessor had left, and he didn’t know where our file was,” he recounts.

Reluctantly, Patrick handed over sh100,000, just to have the file “looked at quickly.” Within days, the missing file resurfaced. “It was right there,” he says, shaking his head. “The moment we paid, it appeared.”

The person in the district land office told him that since Gulu had become a city, all files had to be transferred to the new City Land Board. That transfer, she said, hadn’t happened yet. For weeks, Patrick moved between offices, waiting for coordination between the district and city boards that never came.

Finally, a city land official gave him blunt advice: “Don’t waste your time. Start the process afresh.”

Most times, officials in the land registry ask clients to search for their own files in dusty shelves, and if the files cannot be found, they are advised to begin the entire process afresh, a practice that has angered many applicants.

A visit to the registry of the former Gulu District Land Board offices paints a grim picture: heaps of dusty, abandoned files, some dating back as far as 1962 and 1970, fill the old shelves. Many of these files belong to residents who gave up after years of frustration and endless demands to “start afresh.”

“They have very poor customer care. The last time I went to check for my file, they told me to start the process all over again. It’s so discouraging,” Aluku says with visible frustration.

This was witnessed when the writer followed up on a client’s file while posing as the client. He was advised to either restart the process or search for the file himself. It took him three hours to locate it among piles of dusty, approved files; a hectic and frustrating process. This is how many clients eventually give up on registering their land.

For the elderly like Aluku and Akena, each passing year deepens the uncertainty over their property rights, a situation that leaves them vulnerable to land grabbing, fraud, and emotional distress.

Akena’s frustration deepened when he followed up on his files at the district land registry.

“After three consecutive weeks of checking, they asked me to pay some money. I ended up giving Shs80,000; Shs50,000 for one file and Shs30,000 for the other, just so they could search for them,” he says.

After years of being tossed between offices, Akena finally managed to retrieve one of his files, but not without cost.

“One file has not been found up to now, though I’m still following it up. The other has to reach the land board, and I am now waiting for a response from them,” he explains.

These payments, Akena adds, are never receipted. They are presented as “facilitation” or “appreciation” but have become routine in the system. “Now, even getting your file placed before the Land Board often depends on who you have paid,” he laments.

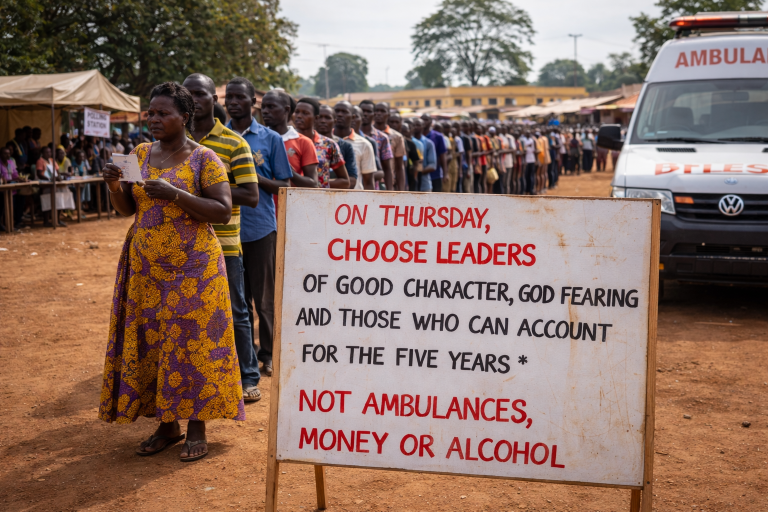

Gulu City Mayor, Okwonga Alfred, acknowledges that some land files have remained unprocessed for over ten years with the District Land Board, but he blames the delays partly on residents who fail to follow up on their applications. According to him, the city has the capacity to handle up to 200 files per month, yet many remain dormant due to a lack of client engagement.

“We call on the owners to follow up,” Okwonga says. “If you leave your file at the district, and the district has handed it over to the city, we can’t start working on it without your involvement. You need to come and move it step by step.”

Voice-1: Gulu City mayor, speaks about backlog of land application files

However, his remarks have not sat well with frustrated landowners, who argue that the problem is far deeper than personal follow-up.

Residents insist that the issue is rooted in bureaucratic inefficiency, corruption, and lack of accountability, not neglect by applicants. “It’s not just about following up,” Aluku noted. “It’s about officials being willing to serve and handle files professionally.

Gulu District Secretary to the Land Board, Oryem Auric, confirmed that the district is still in the process of forwarding more files to the city despite the backlogs.

“We have already sent more than 4,000 files, and we still have more to send,” Oryem says. “But the city says they don’t have enough space to store and manage them.”

A visit to the City Land Board offices paints a different picture, with piles of unattended files stacked in corners and on desks, with little space left for new submissions. Records from the land registry show that Gulu City Land Board has received 8000 files from Gulu district land board since 2023.

Among the files transferred were pending applications, approved files, and those with forwarding letter-instructions to survey the applicants’ land.

Out of the 8000 files transferred to Gulu City, only 3306 have been handled by the City Land Board over the past three years in 29 different land board meetings. With 232 applications for leaseholds and 3074 freehold titles. Officials attribute the slow pace to severe financial constraints that have crippled operations.

This is only 41.3% of the applications forwarded to the board, and it may take more than three years to process such a volume with 5298 files on hand, excluding those yet to be sent by Gulu district land board, which adds to the existing delays and frustration.

Allegations of Bribery

A section of the landowners in Gulu accuse city and land officials of openly demanding bribes to “fast-track” their land title applications.

According to testimonies, these unofficial fees range from small “tokens of appreciation” to millions of shillings, depending on the size, location, and perceived value of the land. Those who decline to pay are often trapped in endless bureaucratic loops; missing files, unexplained delays, and repeated instructions to “start the process afresh.”

Patrick was asked to give sh20m to facilitate the registration of their land measuring 40 meters by 78 meters, something that appears as a dream. This was after he was asked to begin the land registration afresh and apply for freehold.

“He told me, ‘This is a prime land, a very good plot. We can give you a freehold title instead of a leasehold, but there’s a condition,” Patrick says. That “condition” was a bribe: 20 million Uganda shillings.

“They said that money would ‘entice’ the board to pass our file,” Patrick explains. “We gave 5 million first. But they refused mobile money. I had to go to the office on a Sunday evening and deliver it in cash.”

True to their word, after the board meeting, his file was approved. When he took the remaining UGX 5 million, the process suddenly accelerated.

Once the file reached the zonal land office, another series of “unofficial” payments began.

“There was a lady who told me, ‘You return with 250,000.’ But that 250,000 wasn’t receipted anywhere,” he says. “You hide it inside the papers. She checks, sees the money is there, and pushes the file.”

Within three days, his paperwork was cleared and forwarded for titling. What had dragged on for years suddenly moved with lightning speed.

“After paying all that money, everything was done within a month,” Patrick says. “From the village signatures to the final title, all completed. The only thing that had delayed us was the money.”

By the end of the process, Patrick estimates he had spent over UGX 15 million in bribes and unreceipted facilitation fees, with sh10 million paid to bribe the land board to pass his file, not including the official government charges.

Akena Nixon, who has spent years trying to secure titles for his two plots in Kasubi Quarters Cell, says corruption has become part of the process. In 2020, after a field inspection by the Division Area Land Committee, he was asked to pay Shs20,000 additional money to a secretary (Principal Town Agent) to transfer his file to the District Land Board. He had already paid sh300,000 to the area land committee.

“They said it was to facilitate transport for the officer, yet this is a government employee already earning a salary,” Akena explains.

It is the work of the Secretary to the Land Board to forward files of applicants to the board meeting. But for your file alone to be sent to the land board, someone has to pay for it, and for those who refuse, their files have been idle in the land registry for years.

According to a member of the land board who spoke on anonymity, “there is no established structure for how files are forwarded to the board, which gives room for manipulation by those concerned with sorting the files,” he notes.

For elderly residents like Aluku Charles, who has spent over two decades chasing his title, such corruption may explain why his file vanished.

“If your file is not there, where do you begin from? The file is with them,” he says bitterly. “People with money, you see them get their files quickly. If you don’t have money, you keep waiting. You lose hope.”

The pattern of bribery, missing files, and unreceipted payments reflects a deeper rot within the land administration system, one that leaves ordinary citizens at the mercy of officials and agents who exploit their desperation.

The former Chairperson of the Bardege-Layibi Division Area Land Committee, Okwera Santo Comboni, acknowledged receiving similar complaints from residents, including Akena. He confirmed that some clients reported being asked for additional money after their land inspections had already been completed.

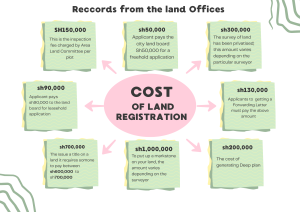

According to Okwera, the Area Land Committee typically charges Shs150,000 per plot for inspections; money that is shared among the five committee members. The funds are meant to cover transport to inspection sites since the committee is not facilitated by the division or city councils. However, these payments are not officially receipted, leaving room for abuse.

“I even held a meeting with the division mayor and the Assistant Town Clerk over allegations of bribery among some committee members,” Okwera says. “Sometimes, when the Land Board returns files for correction, that’s when town agents start asking clients for additional money to ‘help’ resubmit the files. Many landowners simply cannot afford these extra payments.”

Oola Patrick Lumumba, the Mayor of Bardege-Layibi City Division, has acknowledged that corruption in land registration processes has denied many residents the opportunity to register their land within the city.

“There is so much corruption, which is very disgusting. Someone has to pay money at every stage just to move their file. For every step of the process, there is a demand for money. it has almost become an unofficial requirement on top of the official fees,” Lumumba said.

Voice-2: Bardege-Layibi division city mayor Oola Patrick Lumumba shades light to the allegation of corruption in the land registry

The city land board chairman, Owor Arthur, when contacted over the allegation of corruption within the land board offices, referred the reporter to the city town clerk.

However, Innocent Ahimbisimbwe, the Gulu City Town Clerk, reluctantly said he is not aware of the alleged corruption at the land offices. “I cannot say yes or no. If it is there, help represent cases; human beings are human beings, we have to work together,” he said.

Instead, Ahimbisimbwe appealed to journalists to help the City Council expose any cases of corruption that may exist in the land registration processes so that the culprits are prosecuted.

Tony Kitara, a lawyer and land expert, says the crisis in Gulu reflects a mixture of legal confusion and systemic corruption. “These delays are purely corruption. The process of registration is clear and straightforward, from local verification to the area land committee, to the board, and then to the land office. But people are being made to pay for what should be free.”

He adds that complacency by both residents and leaders has enabled corruption to thrive.

“If your leaders are not pushing the Land Board to sit, vote them out. The law allows people to file a writ of mandamus to compel the board to perform its duty. There’s no such thing as a lost file, only a failed system.”

Voice-3: Gulu City lawyer, Tonny Kitara says the applicants can use court to expedite the registration of their land

According to records from the land registry, a client is required to pay Shs 50,000 for a freehold application and Shs 90,000 for a leasehold. These are the amounts officially receipted once payment has been made.

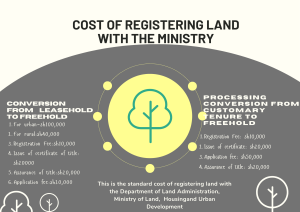

At the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development, the department has outlined the official costs for acquiring land titles as follows: an application for conversion of leasehold to freehold in urban areas costs Shs 100,000, in rural areas Shs 40,000, and Shs 50,000 for the conversion of customary tenure to freehold.

However, clients report a very different experience at the Zonal land offices in Gulu City, where many are allegedly forced to pay unreceipted amounts running into millions of shillings.

“I spent three weeks visiting the office just to have my title printed. I paid all the required fees, but in vain. It was not until I paid more than Shs 2,000,000 unreceipted that I finally got my title,” said a landowner who preferred anonymity. “I later realized I had been cheated,” she added.

Lack of funding

The land officials attribute the delays in handling those files expeditiously to a lack of enough resources in the natural resources department, which has physical planning, environment, land and Surveys, both staffing and finances.

This is constrained by low local revenue collections by the Gulu city Council, the council has managed only to collect sh15.6 billion over the last four financial years as local revenue. City Financial Officer Okot Denis says this is due to tax envision by taxpayers due to poor perception.

In the last four financial years, the department received only sh2.488billion from local revenue collections, urban unconditional grant, non-wages and wages.

Gulu City Principal Land Management Office Mukonyozi Everline says the department does not receive any grant and relies on local revenue for the implementation of the activities.

Oola Patrick Lumumba, mayor of Bardege-Layibi city division, says the problem is worsened by inadequate facilitation for the city’s land office, a challenge that has affected both land titling and urban planning.

“When you look at the city council’s budget for the lands department, it is almost nothing. They don’t even have paper for printing, fuel for fieldwork, or a vehicle for mobility. Without proper facilitation, the planning and management of the city will continue to suffer,” he explained.

Lumumba, states that some residents are frustrated because their areas have not been properly planned, they cannot obtain titles because the roads lack names, and there is no clear block plan.

Voice-4: Oola Patrick Lumumba says the land department is incapacitated to handle planning of the city and registration of the land

Mukonyozi acknowledged that this challenge can only be addressed if the city council prioritises allocation of funds to the department and provides transport to ease the field inspections.

Voice-5: Mukonyozi acknowledges the gaps in the land department

Currently, the Gulu City Land Board runs on an annual budget of just Shs14 million, a figure deemed far too low to manage the workload inherited from the district.

The Land Act 1998 of Uganda, as amended, mandates the board to meet atleast 6 times per year, which means they can sit every two months.

It is only the secretary to the land board who is a salaried staff and other board members only receive allowances after every sitting. The Chairperson of the Land Board receives an allowance of Shs100,000 per sitting, while the other four members are each paid Shs80,000.

This limited funding means the City Land Board can only hold about 30 meetings annually and can only process 6000 files. Each session requires a minimum of Shs420,000 to cover members’ allowances, excluding costs for refreshments and other logistical expenses, but after 3 years, they have handled only 3306 files with only 29 meetings.

Such limited funding has made it difficult for the board to convene regularly, inspect sites, or review pending files, worsening the backlog and leaving thousands of landowners in uncertainty.

According to a member of the land board who spoke on anonymity, the city council has not paid their allowances for several sittings.

The back-and-forth blame between the district and city authorities has left hundreds of landowners in limbo, unsure whether to restart the process, wait for communication, or give up entirely.

City town clerk Ahimbisimbwe Innocent reluctantly said the money is enough, and they will handle it regardless of how long it will take. “If they sit once a month, they will handle some files, but you can’t handle everything; you handle what you can handle,” He notes

Impacts on residents

The persistent delays in processing land titles have left many residents vulnerable to disputes, double sales, and encroachment. Without proper documentation, landowners are unable to prove ownership or defend their property in cases of conflict.

Several residents say the lack of titles has also stalled economic growth at the household level. Without a registered title, they cannot use their land as collateral for bank loans, access government credit programs, or attract investors interested in developing the plots.

“You can’t do anything meaningful with land that has no title,” one Aknea said. “It’s like owning something that doesn’t belong to you.”

The uncertainty has discouraged many from making long-term investments, such as building permanent homes, for fear that disputes or fraud could result in the loss of their property. In some cases, family wrangles have emerged as relatives claim ownership over the same pieces of land, taking advantage of the missing documentation.

However, Gulu City Mayor, Okwonga Alfred, reiterated the city’s commitment to speeding up land registration despite the many challenges his administration faces.

Okwonga emphasized that securing land titles is crucial not only for individual security but also for boosting urban investment and economic growth within Gulu City.

“We are committed to ensuring that people who need land titles get them promptly,” Okwonga said. “If you have a title, you can protect your land and even use it to acquire money for business in the city.”

Voice-7: Gulu City Mayor, OKwonga Alfred reiterates the committeemen to expedite land registration

The Ministry of Lands, Housing, and Urban Development has neither denied nor confirmed allegations of corruption at zonal land offices but reiterated its commitment to “zero tolerance to corruption” in the delivery of services to the public.

According to Denis Obbo, the ministry spokesperson, “Our policy and the government policy that has been communicated to all ministries, including the Ministry of Land, is zero tolerance to corruption.”

Obbo acknowledged challenges in the land registration process, attributing some of them to incomplete documentation submitted by applicants. He explained that delays may occur “because sometimes you see people who do not submit the complete documentation for each transaction.”

He further cited the rollout of new digital systems as another major cause of delays, saying, “We are implementing the digital system, but sometimes there are issues with the digital system not having full information.”

Obbo advised the public to report any cases of corruption or bribery through the ministry’s toll-free line 0800-100-004.

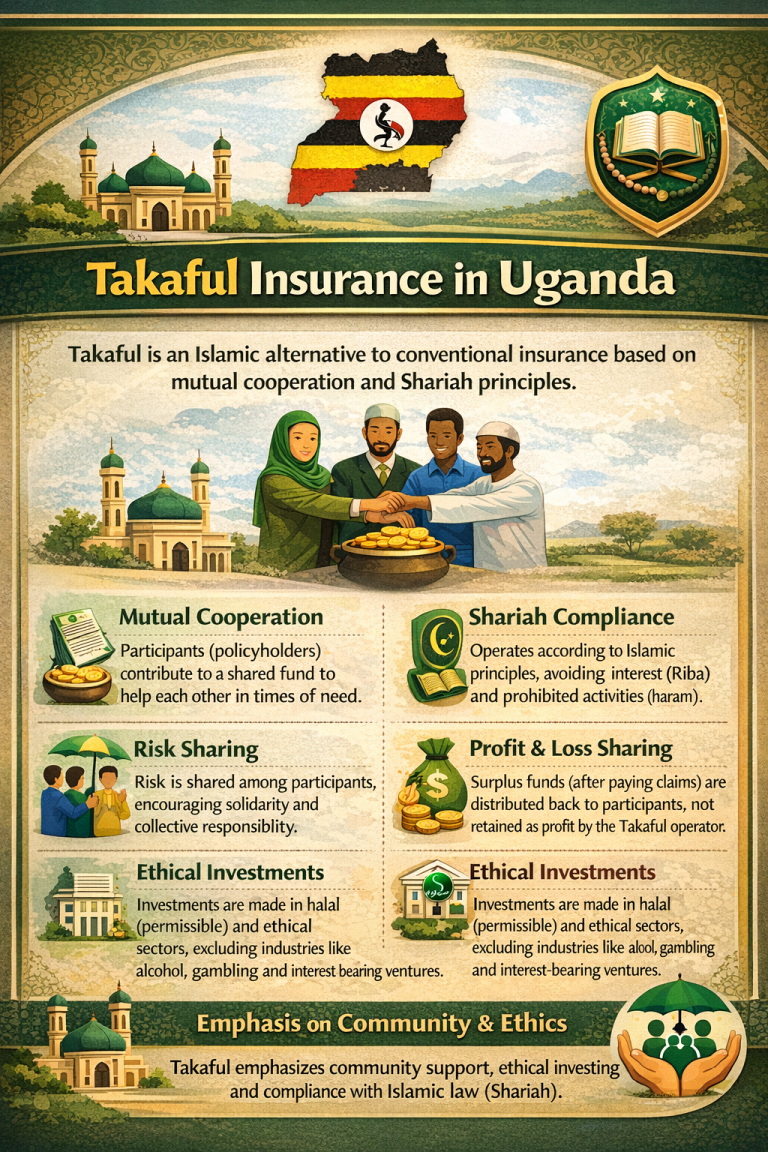

Wider Concerns Over Urban Land Governance

Uganda operates under four land tenure systems: Mailo, Customary, Freehold, and Leasehold. Although the law recognizes them as equal, the customary tenure system remains the most disadvantaged. Unlike the other three, which are governed by the Registration of Titles Act, customary land is guided by community traditions and practices, and it lacks a formal registry.

The current legal framework does not provide for a centralized register of customary tenure, though it allows for the registration of such land at the sub-county level through the Customary Ownership and Registration Authority (CORONA), which issues Certificates of Customary Ownership (CCOs) to holders.

In 2024, Kilak North Member of Parliament Anthony Akol tabled a motion in Parliament urging the House to establish a register for customary tenure and to incorporate customary land interests into the national cadastral map.

That means all the customary land tenure should be properly surveyed by qualified surveyors, rather than Local Council leaders moving around and drawing boundaries manually. The surveyed land should then be reflected on the cadastral map and issued with a certificate of title

In many urban centres, including Gulu City, however, a major historical error occurred. Individuals seeking to formalize ownership of their land were encouraged, or in some cases compelled, to apply for leasehold titles. This was before the 1995 constitution, which restored ownership of public land to the citizens.

Yet, under the current Ugandan land law, a leasehold cannot exist independently; it must be created from an existing tenure. This means that holding a leasehold title does not make the holder the absolute owner of the land, but rather a tenant of the original tenure holder. a situation that continues to create disputes and confusion in cities like Gulu.

Gulu City lawyer and land expert, Tony Kitara, explains that most land within Gulu City still belongs to the original customary owners. He notes that these holdings fall under a customary tenure, which remains legally recognized despite lacking formal titles.

“The land in the city originally belongs to families who hold it under customary tenure,” Kitara says. “Under the current legal regime, if you want to register your land, you are at liberty to do so. provided it genuinely belongs to you. You can choose to convert it into another tenure system and obtain a certificate of title. But under customary tenure, you cannot have a title unless you first go through the legal process of conversion.”

He adds that this process is often misunderstood by both landowners and local authorities, leading to cases where public institutions acquire titles on customary land without full consent or compensation of the traditional owners.

He advises residents holding customary land in the city to convert it to freehold rather than leasehold, since leases are temporary and disadvantageous. “If you inherited your land, convert it to freehold. You’re not renting it from anyone,” he stresses.

According to several landowners, the city authorities have imposed stringent conditions that are nearly impossible for most current landholders to meet. A source who spoke on condition of anonymity because she works with the city council alleged that the move is deliberate, aimed at denying people freehold titles. “I have been trying to convert our land to freehold, but the city authority doesn’t want to issue titles under that tenure,” she said.

Patrick was asked to pay sh20 million to get a freehold title in a prime area within the Laroo-Pece City Division. The case has reignited debate about land governance and accountability in Gulu City, where rapid urbanization often collides with customary ownership systems.

In many parts of Gulu city, residents occupy land inherited from their parents or clans, yet lack formal documentation. This gap has created loopholes exploited by both public officials and private developers.

The Land Act (1998) protects customary landowners from arbitrary acquisition, but enforcement remains weak. Under the law, any transfer of land for public use must be backed by consent, compensation, and a transparent process.